The Régie des alcools era

I was five in 1960. At the time, I had no idea that the following year, 1961, would produce one of Bordeaux’s most glorious vintages of the 20th century. But when you’re five, you drink milk, so that’s exactly where my indulgences began and ended. It wouldn’t be until another quarter century later, while I was a student at the Institut d’oenologie, that I would be able to taste the archetypal great wine while in Girondin. It was a Château Latour 1961. Not bad at all. Yes, I would definitely say that it wasn’t bad at all. I mean, why get hyperbolic about things — it’s just wine.

In Québec, in the meantime, the year 1961 had a completely other connotation: the Commission des liqueurs became the Régie des alcools du Québec. We’ve come a long way. No doubt you still remember the almost clerical ambience of those stores back then, with their caged-in counters that looked a lot like confessionals. No onlooker could possibly have been able to guess either the colour or the shape of the satanic bottle being passed over the counter. “So as to not inflame the desires of consumers,” explained the Thinel report at the very end of the 1960s. This was quite a contrast to the roaring 20s a few decades earlier, when Montréal hosted the most dissolute nightlife on the continent!

Québec in the 1960s

And yet the 1960s hurtled on despite everything with its own electrifying je‑ne‑sais‑quoi. It had a certain teenybopper energy, as testified by the many bands of the early 1970s, like César et les Romains, Les Hou-Lops, Les Lutins, Les Bel-Canto, Les Sultans, Les Sinners, and Les Excentriques. It was a decade in which I discovered, like many of you — come on, admit it! — my parents’ liqueur cabinet, a place reined over by the ubiquitous Martini & Rossi, a range of gins including the unmissable Tanqueray Dry, the instantly recognizable bottle of Grand Marnier, and don’t forget the unusual Tesoro Amontillado Medium Dry from Spain. These were “intimate” encounters of the kind you could not come out of completely unscathed, to say the least.

The 1960s revolution wasn’t all that quiet, which would no doubt please Jean Lesage, the premier of Québec at the time. For any of you feeling nostalgic for the decade, I’d like to remind you that the Montreal Canadiens won four Stanley Cups (1965, 1966, 1968, and 1969), Michel Tremblay wrote Les Belles-soeurs, which garnered him the reputation he still has today, the Cyniques were using their dark humour to poke fun, scorch the ears of listeners, and raise consciousness, the Classels were all the rage, and, in the meantime, France was the site of seven weeks of massive unrest during the May 1968 demonstrations. None of which prevented American Neil Armstrong from calmly taking the first steps for mankind on the moon one year later, in 1969.

Expo 67: A window to the world

Between the surge of Beatlemania and John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s 1969 bed‑in, the 1967 International and Universal Exposition in Montréal made its appearance — and no less exciting was the fact that you could get there by taking the brand new underground metro that ran on rubber tires. One crowd-pleaser was the fact that once inside the Exposition you needed to have your “passport” stamped every time you visited a pavilion. Expo 67 not only highlighted gastronomical riches from around the world, it also widened Quebecers’ horizons when it came to wine. At that time, we had to content ourselves with a mere thousand-or-so products (1,014 to be precise) supplied by the Régie des alcools. In 2020, that number increased 16 fold, not including private import products, which would double that figure. What a trip it’s been!

After years of retail outlets featuring wire mesh, the first “semi-libre-service” branch was launched at Place Ville Marie in Montréal in 1960. Customers were finally allowed to see and select their own products.

Modernizing the Régie

The decade between 1960 and 1970 quietly led to a modernization of the Régie des alcools’s facilities and business model, with the opening of the first “semi‑self‑serve” retail store in Place Ville Marie in Montréal being one example. Practically a revolution, you could say. But while some items were presented on shelves, the wine hadn’t yet completely come out of the closet, as it were. But a few rays of light were starting to pierce that darkness. While the infamous counters were still there, customers were now allowed to see the products they were looking for, despite not being able to reach for them on their own. This last mile wouldn’t be covered until 1970, when self-serve outlets would allow customers not only to see the products they wanted, but take them in hand, coupled with a much wider selection of wines, though stronger fare was still very popular. This was the context in which the first permits to produce and sell Québec wine were awarded.

These permits were justified under the directorship of judge Lucien Thinel, who from 1968 to 1971 was mandated with “investigating the alcoholic beverage trade and researching the most efficient and economical ways to ensure the surveillance of said trade in order to proceed with order, and secure revenue essential to Québec’s development, in the form of taxes or other.” The recommendations of the Enquiry Commission led to the enactment of two laws in 1971 whose intent was to split the Régie des alcools into two distinct organizations with two different mandates.

The two pieces of legislation that were swiftly tabled were: bill 44, which called for the creation of an alcohol permit control board, a legal entity that would oversee issuance and cancellation of permits (which all restaurateurs and other sellers of alcoholic beverages must respect to this day by ticketing their bottles); and bill 47, which authorized the alcoholic beverage trade by permitting the purchase, importation, bottling, distribution, and sale of alcohol within the territory of Québec. Out of this second piece of legislation the Société des alcools du Québec (SAQ) was born, the same organization we all know today.

While all this might seem a bit drily administrative, to say the least, these laws in fact established the SAQ as an exclusively commercial business that emphasized “efficiency and public service” while simultaneously ensuring it greater autonomy, not to mention, as recommended once again by the Thinel commission, “some respite from any political pressure.” This attracted criticism from its detractors, who would constantly question the existence of such a monopoly, frequently arguing that its prices were too high, or that its product selection was limited, or even that its distribution method was anarchic or its buyers’ ability to react to demand was not fast enough to match the speed of international business.

No doubt as a system it is not perfect, but with all due respect to these same detractors, it should be recognized that consumers contribute to the dividends transferred to the government by THEIR Crown corporation. It should also be remembered that we have moved far beyond the store ambience described in 1971 in the Thinel report (specifically on page 236), which commented that “the customer sometimes has the impression of being treated like an intruder who is disturbing the peace of employees” when entering the store. Today, the SAQ’s wine advisors — and there are some truly passionate people on our team! — are always happy to share their knowledge with customers.

Ladies welcome

In 1979, almost 40 years after obtaining the right to vote in Québec, women were granted the right to patronize bars, or “taverns” as they were called. But while the glasses may well have been “sterilized,” that didn’t mean their 25‑cent frothy ales, consumed in a testosterone-laden atmosphere, contributed at all to making such establishments “female-friendly.” And were women for their part at all enticed by these types of places, where 7 a.m. boozing was de rigueur? Not really, no. Too little, too late. Instead they found their way into brasserie-type establishments that were friendlier, and where in later years the habit of enjoying a glass of wine would develop into the custom that is still popular to this day.

In 1973, the SAQ inaugurated the first Maison des vins at Place Royale, in Québec City. There, customers could choose from a vast selection of high-quality wines.

A taste for wine

The number of stores multiplied, while in 1978 the provincial government allowed independent grocery stores and convenience stores to offer a selection of Québec wines to their customers, since local wines were taking their first timid steps towards popularity, despite the fact that the industry was still in its early phases. By allowing grocery and convenience stores to sell wine, the hope was that Quebecers would develop a taste for it, thereby increasing consumption. Bacchanalian associations, private wine importation companies, amateur tasting clubs and, soon, the province’s first major wine guide, created by Michel Phaneuf (1980), capped off the decade while at the same time opening up new vistas as well as new strategies for development for the SAQ. This led to the creation of a number of banners (Express, Classique, Sélection, etc.), thereby segmenting a market that had become more diverse than ever before.

With the Phaneuf guide — which celebrated its 40th anniversary in 2020 — a new golden age of wine had begun in Québec. This is the period in which I personally found my bearings, and when — and I mean this without intending any fawning over the SAQ — I practically travelled the planet through my purchases of the many wines available in its stores. This was a learning experience, and a sizeable advantage, that our French cousins across the ocean could not enjoy. While we might all start off drinking milk when we’re five, the fun doesn’t have to end there!

What were we drinking?

Cocktails

Did you know that La Ronde’s Bulldog Pub, in 1967, was the first to offer single malt whiskies and British beer? The period was soaked in the heady perfume redolent in series like Mad Men — it was like Don Draper and his intoxicated drinking buddies living out the booziest reality TV series you’ve ever seen. Cocktails prevailed, and every office, meeting room, and reception area boasted a well-stocked mini-bar supplied with Melchers Special Reserve, six-year Biscuit cognac, De Kuyper gin, Canadian Club, Crown Royal, Moskovskaya vodka, and other spirits that could be concocted into a martini, gin tonic, Zombie, Singapore Sling, Bloody Mary, Cuba Libre, Negroni, Mai Tai, Old-Fashioned, or Whisky Sour, to name just a few. Even at 10 in the morning, no less!

As if that weren’t enough, you could continue the party over dinner at the Beaver Club or the Kon Tiki (both christened in 1958), where the establishment’s trolley could make a stop at your table to help you alleviate the effects of premature dehydration, maybe with another three martinis — just so you could manage to get back to the office, of course. Though that would be after a tipple of trendy St-Georges Bright Canadian port (!) or a li’l Bols crème de menthe for the road. That bitter taste in your mouth? Don’t worry, you can power-nap the pain away back at the office.

Nostalgia

It’s 1955. New opening hours have been set for 11 stores, giving you the possibility of picking up — even at the late hour of 10 p.m.— this 1949 Bichot Pouilly-Fuissé for $2 (compared to $26 today), this Taittinger Brut champagne for $5.75 (compared to $65.25), or this 1950 Côte Rôtie for $2.15. As I write these lines, the Côte Rôtie La Turque 2010 from Guigal retails for $472 at the SAQ’s very chic Signature store, which is almost 220 times more expensive than in 1955. But I would also like to express one regret: the disappearance of good old Québérac for 85 cents a bottle!

Cocktail memory

A cocktail that’s emblematic of Canada, the Bloody Caesar was first created in Calgary in 1969 when bartender Walter Chell took his inspiration from a plate of pasta with clams, a dish called spaghetti alle vongole. He created his cocktail by combining clam juice with tomato juice, then added vodka and spices.

Bloody Caesar

Makes 1 drink

Ingredients

45 ml (1 1/2 oz.) vodka

120 ml (4 oz.) Clamato juice

5 ml (1 tsp.) Worcestershire sauce

A few drops of red Tabasco sauce

1 lime wedge

Celery salt

Ice cubes

Salt and pepper

1 sweet pickled onion

1 celery stalk

1 small pickle

1 small hot pepper

Preparation

In the glass

Rim a highball glass with the lime and celery salt, then fill glass with ice. Add all the ingredients, except for the vegetables. Stir using a mixing spoon. Season with salt and pepper to taste. Garnish with the celery, pickle, hot pepper, and onion, if desired.

What were we eating?

Da Giovanni

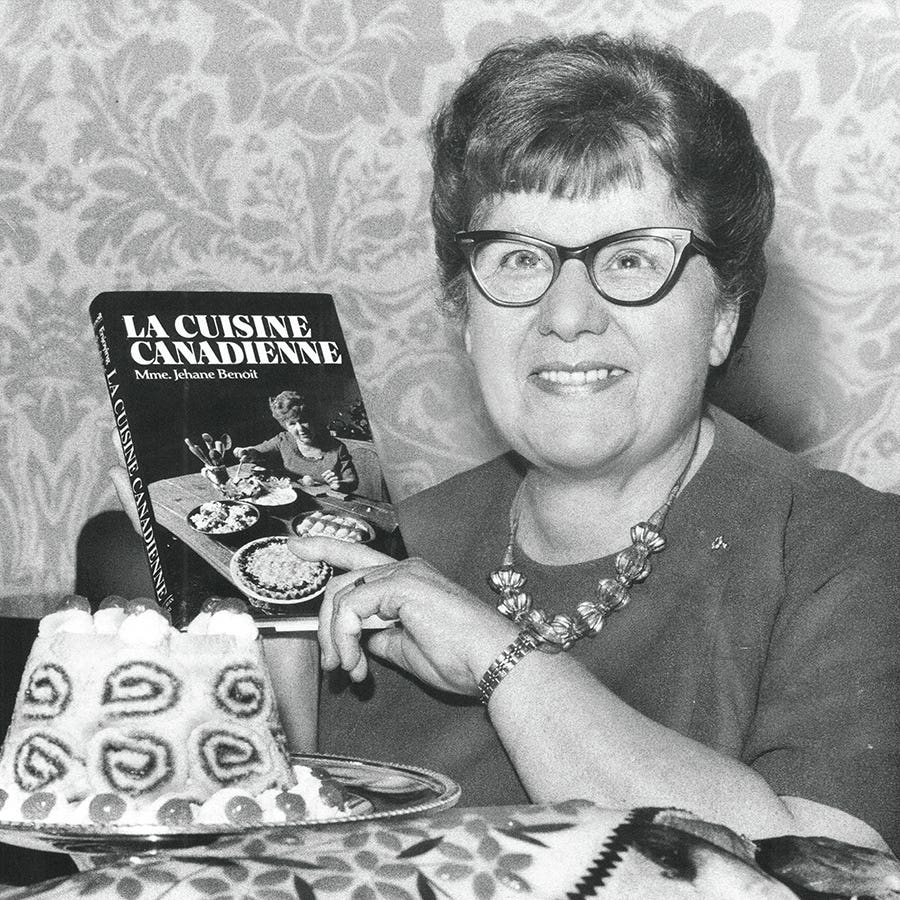

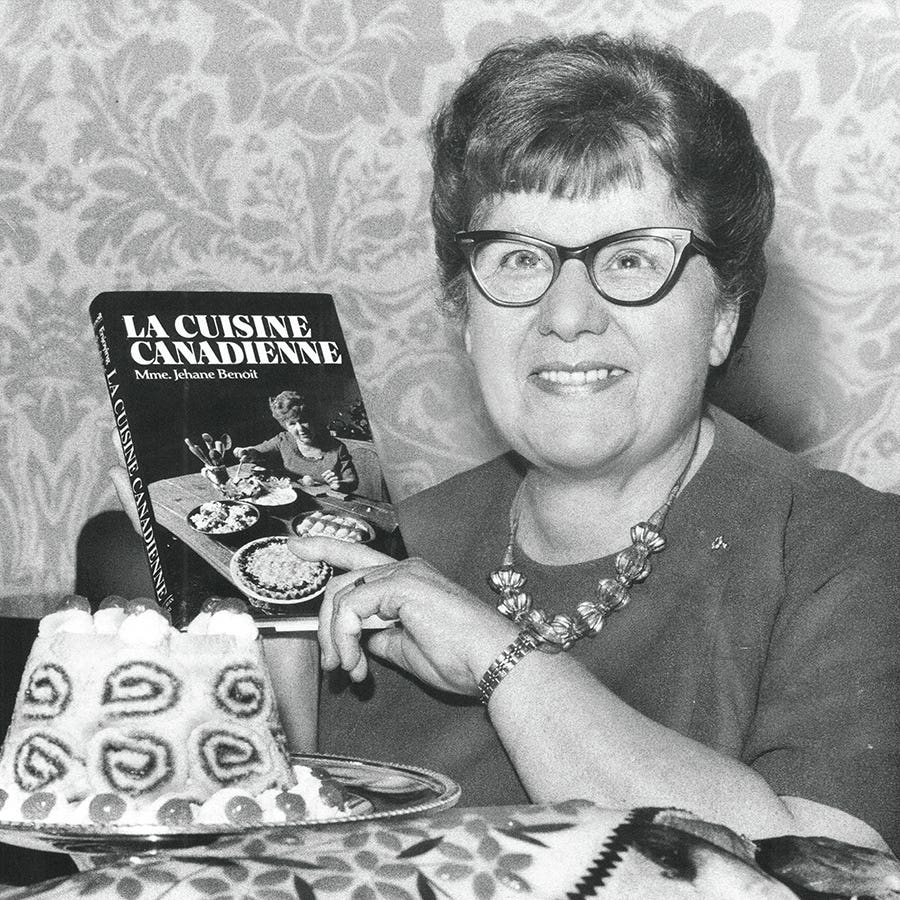

Personally, whenever I would happen to hear “Da Giovanni, Da Giovanniiiiii... le meilleur spaghetti...” I was incapable of ridding myself of that earworm refrain. In the 1960s, the Sainte-Catherine street restaurant in Montréal offered its famous pasta, which was not remotely al dente, smothered in a waterfall of meat sauce. And yes, spaghetti was the star of the show: cheap, filling, popular — the place had the best recipe — especially when served with a straw-covered fiasco of Chianti Ruffino. The inescapable spaghetti competed for popularity with other simple, economical dishes, like pâté chinois, pea soup, turkey, tourtière, and pouding chomeur. But this was all before Jehane Patenaude Benoît, trained at the Cordon Bleu in Paris, published her thirty-or-so tomes, including the celebrated Encyclopedia of Canadian Cuisine (1963), with the goal of widening Quebecers’ gustatory horizons. She launched a plate-sized revolution at a time when Quebecers were travelling more, especially to Paris, where they sampled foie gras, veal kidney, vol-au-vent, duck breast, marrowbones, and Bresse chicken. This was a big difference from the TV dinners consumed on the plane in 1962, which would always be followed by a cigarette. Luckily, imbibing these delicacies wouldn’t always involve such long, expensive trips, since on December 19, 1980, the Parisian-style bistro L’Express opened its doors on Saint-Denis Street in Montréal. What a blessing! Just ask Soeur Angèle!

Recipe memory

The dish pain sandwich appeared in Québec between 1920 and 1940 in ads for spreadable cheese. Over time, the recipe became a Christmas tradition alongside tourtière and turkey. It originally featured a loaf of bread sliced horizontally, then garnished with alternating layers of chicken salad, ham salad, and egg salad.

Layered sandwich loaf

Preparation 30 to 45 minutes

Cooking time 12 minutes

10 to 12 servings

A staple of Canadian cuisine

Jehane Benoît’s legacy in Québec gastronomy is immense. Having published 30 or so books and maintaining a presence on radio and TV during the 1950s, this graduate of the food chemistry program at the Sorbonne in Paris influenced many generations and chefs across Canada. Her most well-known work, the Encyclopedia of Canadian Cuisine, published in 1963, sold over 1.5 million copies. Recognized for her progressive personality, she introduced wine and other kinds of alcohol into Québec cuisine, lent a modern touch to traditional Québec dishes, and opened Quebecers to the world of international cuisine.

Photos: SAQ archives (Régie des Alcools du Québec and Maison des vins); Myriam Huzel (women); QMI Archives / Media (Da Giovanni Restaurant); Valeria Bismar (cocktail and recipe).

Free in-store delivery with purchases of $75+ in an estimated 3 to 5 business days.

Free in-store delivery with purchases of $75+ in an estimated 3 to 5 business days.