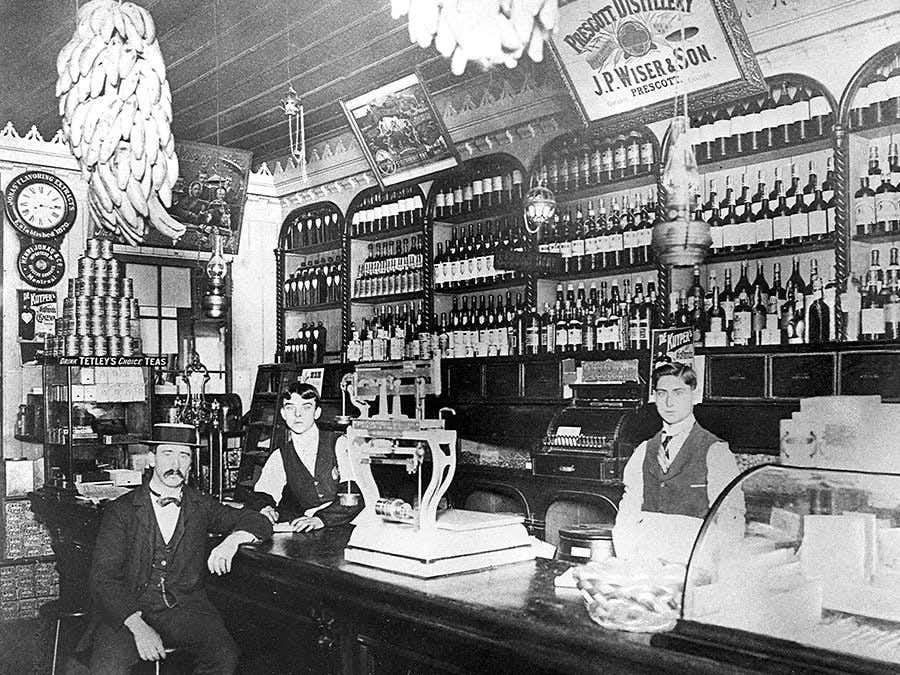

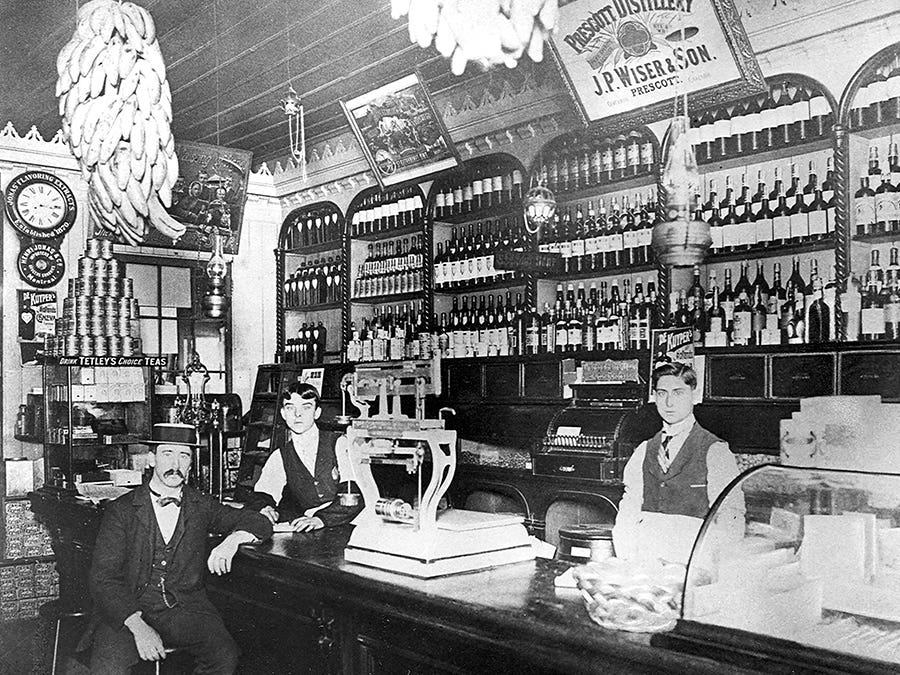

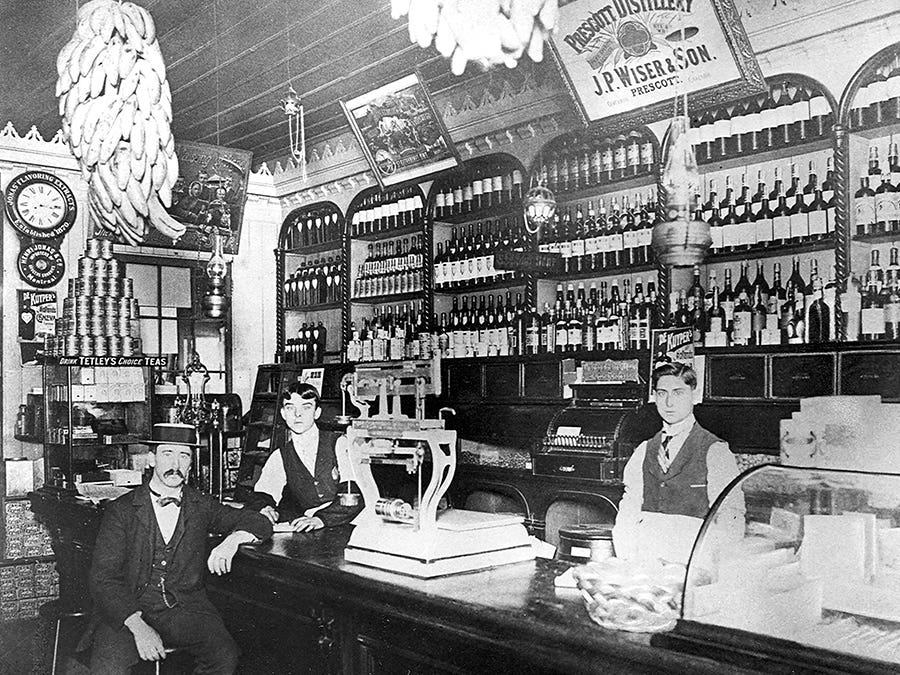

At the end of the 19th century, a temperance movement was born in the United States, in Canada, and even here in Québec. It was a very simple idea: limit, if not abolish, the sale and consumption of alcohol.

By historian Laurent Turcot / Photos: Archives SAQ

In the United States and Canada, alcohol was considered the evil of the century, encouraging workers to fall victim to the worst vice, taking them away from their domestic duties and hindering their Christian morality. In short, society feared the effects of alcohol, which was becoming more and more accessible. One word was on everyone’s lips: prohibition.

In the United States, the Volstead law was adopted in 1919 and enacted in early 1920. The production, distribution, and sale of any products with alcohol levels greater than 0.5% was prohibited. Contraband took hold of the market, and gangsters such as Al Capone, Lucky Luciano, and Bugsy Siegel took control of different territories. The alcohol industry became the main focus of the American mafia, who would turn to Canada for provisions.

Rebellious Montréal

In Canada, the situation was complicated. While the temperance movements were just as active, the methods for abolishing what was then considered an evil vice were somewhat different. In 1850, the Act for the suppression of intemperance was put forth to better support the alcohol industry. Then, in 1864, Dunkin law allowed the different municipal authorities to prohibit the sale of alcohol. However, to ratify such a law, a majority vote during a referendum was required.

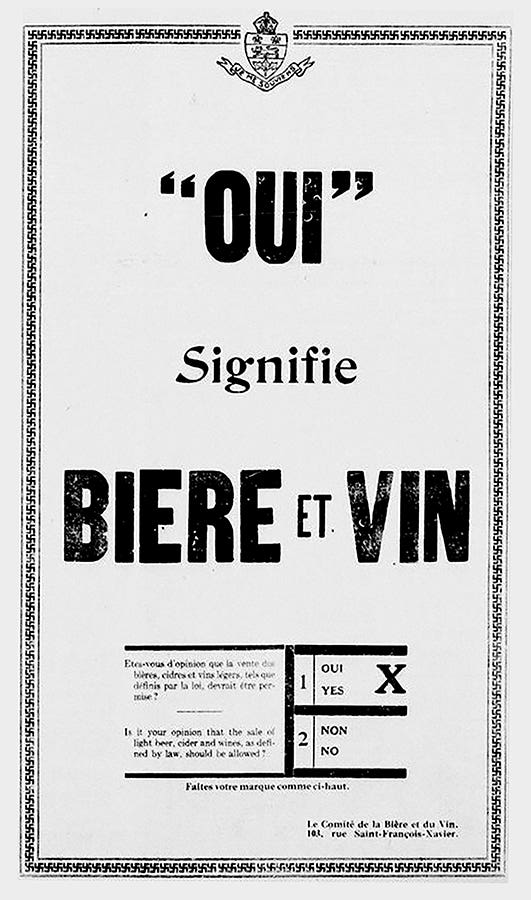

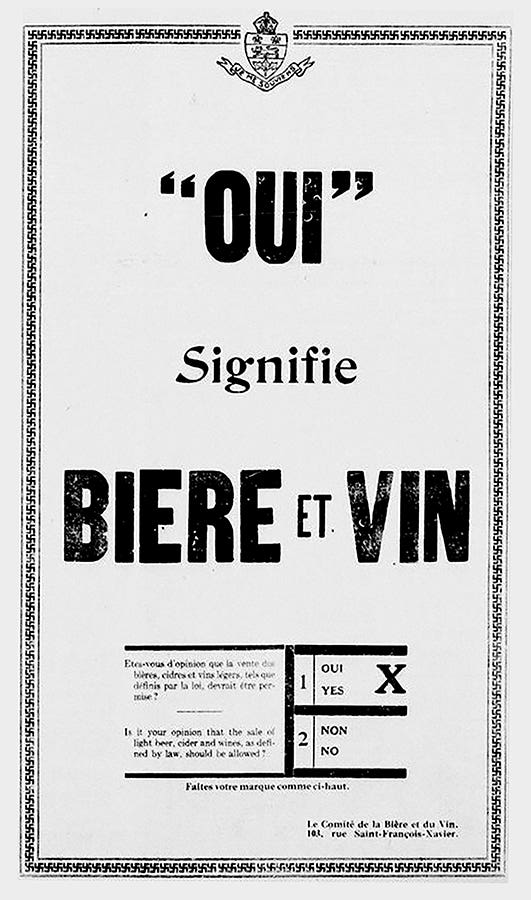

A few years later, in 1878, the Scott Act was added to reinforce the Dunkin law, setting out that if 25% of voters in a given municipality requested a referendum on the matter, said referendum would be held. Over the years, several municipalities chose to offer their population the chance to vote on the prohibition of alcohol sales.

In 1919, nearly 90% of municipalities in Québec – close to 1,150 cities – were considered “dry,” as prohibition reigned. In Trois-Rivières and Québec City, alcohol was banned, but in Montréal and Hull, citizens were free to purchase and consume it. As of the 1920s, Montréal was thought of as the Paris of the North. Jazz musicians from New York and Chicago, the likes of Count Basie and Duke Ellington, would flock to Montréal to perform in the Red Light District, where alcohol poured freely. Police and city officials would turn a blind eye on these activities for quite some time; corruption by the mafia was a part of everyday life.

Québec says no to prohibition

The pressure on the government of Québec from the temperance movements, as well as from the clergy, was increasingly stronger in the early 1920s: they were demanding a ban in the province at large. In other parts of Canada, it was already a growing trend. In 1916, Alberta voted in favour of the ban, with Manitoba and Nova Scotia not too far behind. And that’s not all: In 1917, British Columbia and New Brunswick also followed suit.

The prohibition wave made its way to Québec. In 1919, Premier Lomer Gouin prohibited alcoholic beverages across the province. However, following a referendum, Quebecers voted in favour of excluding beer, cider, and wine from this new prohibition law. Thus, the population was still able to consume products with alcohol levels inferior to 2.5%. Big-name brewers such as Labatt, Molson, and Sleeman, adapted to this reality and began producing temperance beers with just 2% alcohol.

This new law would only last two years. Contrary to other provinces Louis-Alexandre Taschereau’s government would adopt a particularly unique position by establishing the predecessor to what is today known as the Société des alcools du Québec. Instead of cutting off alcohol completely, the State decided to exercise control over the sale of alcohol and oversee its supply. This would become the first governmental system of control over alcohol in North America. In fact, in the Commission’s first annual report, it was stated that:

COCKTAIL MEMORY

Photo: Valeria Bismar

Caribou

Near the end of the 19th century, drinking mulled wine had become an established custom. For some, the Caribou is a Canadian version of mulled wine, for others, it’s a classic Québec cocktail. By 1955, it had become a veritable trend thanks to the Québec Winter Carnival.

Learn more about this era and the creation of the Commission des liqueurs

Photos: Archives SAQ

Free in-store delivery with purchases of $75+ in an estimated 3 to 5 business days.

Free in-store delivery with purchases of $75+ in an estimated 3 to 5 business days.